By Madison Knoblock

In the scientific community, the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, related to the mustard greens family, is the lab rat of all plants. Because of its relatively small genome, it was the first plant to have its genome sequenced and since then has become a vital tool in research of the molecular biology of plants. So, this Eurasian native seemed the best candidate for a spot on a SpaceX mission to study plant growth in space.

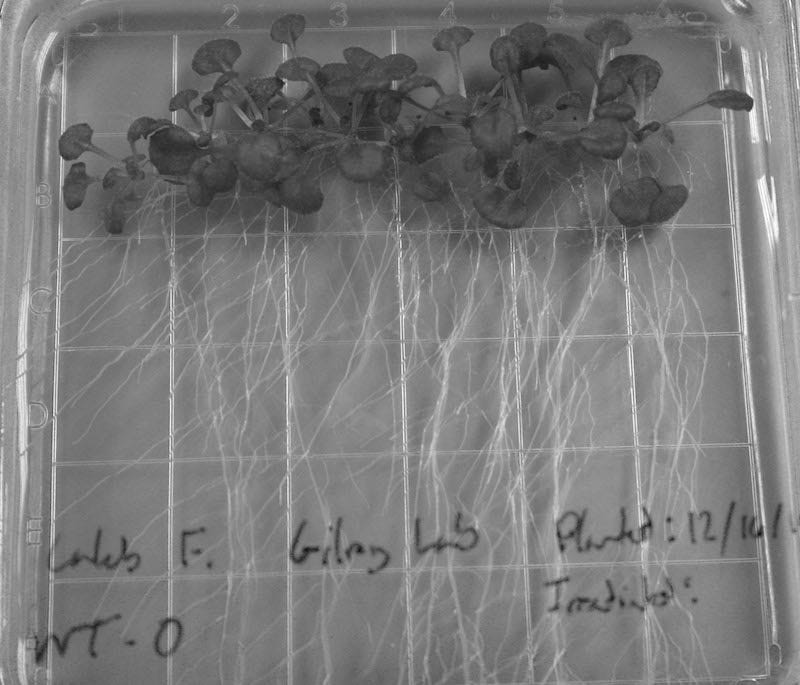

In 2013, NASA sent 1,200 Arabidopsis seeds to the International Space Station, where they germinated and began to grow. Before anything else could happen, plant growth was chemically halted, frozen and returned to the lab of Simon Gilroy, a professor of botany at UW-Madison. Gilroy and his team proceeded to concentrate and purify the RNA of the seedlings, preparing them for the RNA Seek machine, which read and organized its 30,000 genes at UW-Madison’s Biotechnology Center.

Before the partnership with NASA, Gilroy’s team had been studying how plants respond to environmental stresses like wind, flooding, gravity and radiation. The researchers were trying to understand how plants detect and respond to these stressors. “For example, when a field gets flooded, the crops die because they run out of oxygen. But, they can last up to 3 days waiting for flooding to recede, where humans would last only seconds [without oxygen],” says Gilroy. Plants are aware of flood conditions and can sense when they are in a state of low oxygen. After identifying these environmental factors, the plants are able to defend themselves.

This research coincided perfectly with a problem Gilroy predicted NASA would run into when they recently grew red lettuce in the space station. Watering plants is no longer a fill-up-the-can-and-pour kind of job. Without gravity, the water will not pour or sink through soil. Gilroy says, “You can use a syringe and force water into the soil, but because of capillary forces, surface tension and adhesion, the water becomes sticky. So if you water a plant in space, the water will stick to and cover the roots, and a plant covered in water is flooded.”

Another problem Gilroy was concerned with was how plants respond to cosmic radiation. Imagine a star exploding and its particles hurdling through space at near light speed. Cosmic radiation occurs when those particles pass other exploding stars and continue to accelerate, explains Gilroy. The Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field shield us from cosmic radiation, but the astronauts and plants in space are completely vulnerable, even in a space shuttle. Cosmic radiation can damage the astronaut’s cells, and possibly cause cancer. However, space agriculture has also proven to lessen those effects. Antioxidants in blueberries and strawberries have proven to counteract short-term cosmic radiation in rats, which explains the red lettuce (also high in antioxidants) that was also recently cultivated on the space station.

The goal of growing Arabidopsis in space was to compare its 30,000 genes, profiled by the RNA Seek machine, to those of and Arabidopsis plant grown on Earth. Gilroy and NASA want to know which genes become more or less active in microgravity, and how plants can be engineered to thrive under these conditions.

Agriculture in space is imperative to sustain life for a long period of time, like an eight-month mission to Mars. Available storage space is a currently limiting factor on small spacecraft, but would increase if astronauts didn’t have to store freeze-dried food packets. Packets of seeds are much more efficient to store than the food packets, and plants that reproduce can supply endless nourishment long after food packets run out. A potato plant engineered to endure harsh space conditions may be the difference between a successful mission and starvation. NASA and Gilroy are working tirelessly to discover the secret of a plant’s relationship to its environment in hopes that when the time comes for a Mars mission, the astronauts can bring a little piece of Earth along with them.