By Mark Bodnar

During childhood, just about everyone received an unfortunate nickname or two that they are quite glad to have left firmly in the past; and fortunately, time does have a certain knack for erasing things from memory. Today most people know Illinois as the Prairie State and Wisconsin as the Badger State. But Illinois developed another nickname that few people remember today. This is the story of how Wisconsin came to be known as the Badger State and how our good neighbor Illinois acquired the less illustrious nickname, the Sucker State.

The story behind these nicknames began in the 1820s before Wisconsin even existed as a state. At the time, it was just the northwestern frontier of the United States. Southern settlers of the frontier regarded the area as a cold, barren wasteland with winters that were inhospitable for settlers. However, this attitude changed abruptly in 1825 when lead was discovered in present-day northern Illinois and southwestern Wisconsin. Suddenly, Wisconsin became the land of opportunity, and thousands of prospectors flocked to its acclaimed lead reserves for the chance of striking it rich on the ‘grey gold.’ The ensuing influx of people was actually quite similar to the 1848 California gold rush, except perhaps a bit colder and a tad more barren.

The first folks to make their way up to the rolling prairies of modern-day southwest Wisconsin were from Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee. They were prospectors, not settlers, and they had no intention of staying permanently through the bitter winter in a foreign land. These were adventurous people who were just looking to pull lead from the ground, get rich and get out. They were motivated mainly by money and had evidently not invested much time considering the particulars of mining lead. In fact, most all of these early prospectors had no experience mining and lacked the necessary knowledge and tools. Nevertheless, they proceeded in large numbers, armed with shovels and rifles, to the promised lead reserves to start digging holes.

And quite literally, digging holes is exactly what they did. The best method the early prospectors had for locating lead was to burrow into the ground at random until they hit bedrock or struck a vein of lead. These exploratory holes were later found littering the landscape with some as far north as the Baraboo hills, an area that doesn’t contain any lead. One miner from the time described prospecting as “a good deal like a lottery — a hundred chances to lose where there was not one to win.” Few prospectors in the region mined enough lead to make money, and like a lottery, the few that did succeed reinvigorated the efforts of the rest. Each spring, crews of men could be seen trekking north through Illinois to play the original Wisconsin lottery.

In addition to their assessment of the land being rather cold and barren, there was another reason these prospectors did not plan to stay in Wisconsin. Technically, they were trespassing on Ho-Chunk land. The Ho-Chunk had been mining the lead reserves for many years and they did not appreciate the prospectors’ invasion of their land. Tensions erupted in a brief conflict, later called the Winnebago War. It began and ended so quickly that some prospectors ignored it completely and continued on mining. At its conclusion, the United States agreed to investigate the Ho-Chunks’ grievances regarding the trespassing lead miners. However, it was not enforced and thousands more miners came to the area after the war ended.

This renewed influx of prospectors consisted of not only adventurers from the south; there was a new type of miner with different motives that began to settle in Wisconsin. They were primarily from the east coast of the U.S. and Cornwall, England. In contrast to the early prospectors, they planned to settle permanently in Wisconsin. The Cornish in particular were experienced miners and brought with them tools that allowed them to dig deeper and extract massive quantities of lead from areas abandoned by the early prospectors. This wave of permanent settlers marked a notable change for Wisconsin: it was no longer only a land for prospecting but also a place that held promise for settlers.

Thus, two distinct groups emerged in the lead mining lands — those who stayed through the winter and those who returned to the south. This primarily divided the get-rich-fast prospectors from the south and the more pragmatic, experienced miners from England and the east coast. From this division came the well-known nickname for Wisconsin, the Badger State, and and less familiar one for Illinois, the Sucker State.

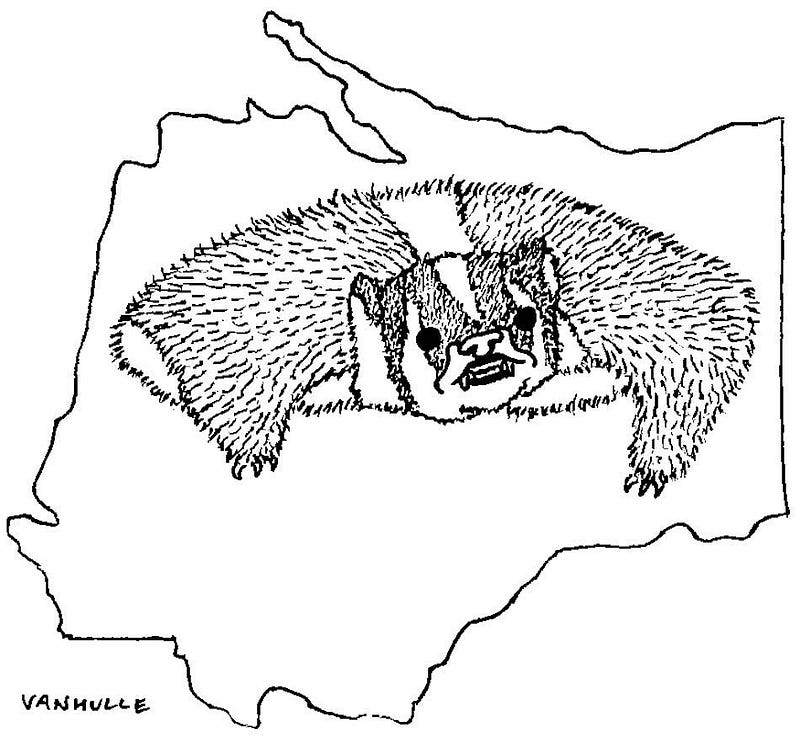

The origin of the badger nickname has at least two possible explanations. One story is that the more experienced miners gave the name to the southern prospectors because of their haphazard method of searching for lead. Since the method had a low likelihood of success, prospectors did not waste effort constructing a permanent home, but instead used their holes as temporary shelters. Other settlers considered the digging of these holes to be rather foolish. They heckled the prospectors, calling them ‘badgers’ and their temporary homes ‘badger holes,’ due to the similarity of their living arrangements to the animal. This rendition of the story has the interesting implication that the original badgers were actually from Illinois.

Another explanation asserts that the southern prospectors called the permanent settlers ‘badgers’ because they remained up north in Wisconsin through the winter. The southerners chose the nickname ‘badger’ because they were not accustomed to the animal in the south and so they associated it with Wisconsin.

The unfortunate nickname that befell Illinois came about in a similar way. Permanent settlers noted that the return of miners from the south to Wisconsin each spring coincided with the northern migration of a fish known as the suckerfish. The transient southerners thus became known as ‘suckers’. Some accounts also assert that the exploratory holes dug by prospectors were called ‘sucker’ holes, not ‘badger’ holes. This would offer an interesting explanation for why the word ‘sucker’ is now used to mean gullible.

Thus, when miners gathered during the winter in Wisconsin and someone asked the whereabouts of another miner, the response would often be, “He’s gone south, but he’ll be up with the suckers in the spring.” Similarly, when the southern miners returned north in the spring they would tell others, “We are headed up among the badgers.”

Over time, Wisconsin became known as the Badger State, and Illinois as the Sucker State. Evidently, Illinoisans did not embrace their nickname with the same vigor as Wisconsinites, but history still bares the truth. In the ongoing rivalry between our states, it is obvious that Wisconsin came out on top in the battle of nicknames at least.